It's beginning to come into focus how much raw materials it will take to transition to a net-zero economy and how woefully prepared we are.

Governments are fast at work at re-writing legislation forcing people and companies to use greener energy but there's little action being taken to make sure there is the capacity for change.

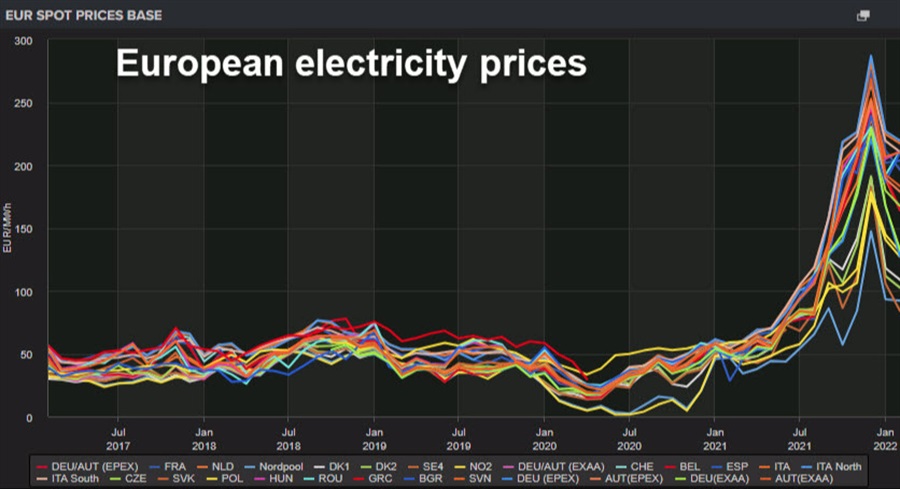

What happened in Europe with power this winter was the opening silo. A week of windless days, cloudy skies and cold weather tipped the scales and upended industries because there wasn't enough capacity in fossil fuel-powered generation. It turns out that if you build a grid around wind and solar, you need parallel generation for when it goes down.

So now instead of building one system, you need two and all the resources that go along with it.

There's also the shifts from changes. Nissan today said a set of guidelines around auto emissions in Europe called Euro 7 means it will abandon ICE car development in 2025. Many jurisdictions have already put in rules or guidelines to ban new ICE car sales by 2030.

For one, that will put a fresh strain on the power grid.

But equally important might be what it does for metals. While an electric car doesn't need gasoline, it needs far more copper, lithium and other metals.

Today, Goldman Sachs was out with new copper forecasts that show deficits growing through 2025. Copper prices are already near generational highs and inventories are rapidly shrinking.

The problem is that a greenfield copper project takes 5-7 years in development and permitting before you get anything out of the ground. So even if prices go parabolic from there, the supply response is half a decade away.

On top of that, the same movement that's pushing greening is also slowing permitting of green metals. The most-egregious example is the Lithium Americas mine in Nevada at Thacker Pass. It would be the largest lithium mine in the US but after a decade of development a judge blocked it to protect sage grouse habitat.

On top of all this, the greening will need tremendous amounts of steel, concrete, lumber and other manufactured goods. Supply chains will need to be rebuilt.

It's all extremely costly and resource intensive.

Last month, a little seen speech from ECB Governing Council member Isabel Schnable outlined the true costs:

While in the past energy prices often fell as quickly as they rose, the need to step up the fight against climate change may imply that fossil fuel prices will now not only have to stay elevated, but even have to keep rising if we are to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement

Financial institutions and banks are being heavily pressured to reduce investments in fossil fuels but we're already starting to see the results. Even now with crude at $90/barrel, medium-size oil companies with negligible amounts of debt are charged far more than similar companies to borrow.

The combination of insufficient production capacity of renewable energies in the short run, subdued investments in fossil fuels and rising carbon prices means that we risk facing a possibly protracted transition period during which the energy bill will be rising, Schnable said.

The ECB is now finding that the price of fossil fuels quickly filters through to the price of power and then into nearly every good.

Her main point though was that the energy transition is an upside risk to inflation. I think few other central bankers have realized just how large this risk is. Moreover, the eventual public reaction will be intense and divisive.