There is a great Martin Wolf article in the Financial Times that laments the slow growth in the world economy.

He cites recent comments from US Treasury Secretary Jack Lew about slow growth in advanced economies. Noting that US GDP is about 6% higher than before the crisis, Japan and the UK are about 2% higher and the eurozone is 4% below its pre-crisis level.

What Mr Lew did not add is that this feeble performance – even the 6 per cent rise in real demand in the US over more than six years is pathetic by historical standards – occurred despite the most aggressive monetary policies in history.

And what Mr Wolf did not add is that combined with that monetary policy was some of the most expansionary fiscal policy in history.

- US total public debt has risen to 106% of GDP from 66%.

- Japanese debt-to-GDP has risen to 226% from 170%

- Eurozone debt-to-GDP has risen to 91% from 70% (Spain to 100% from 36%)

The takeaway is simple: If that couldn’t get economies moving, near-zero growth isn’t going to go away.

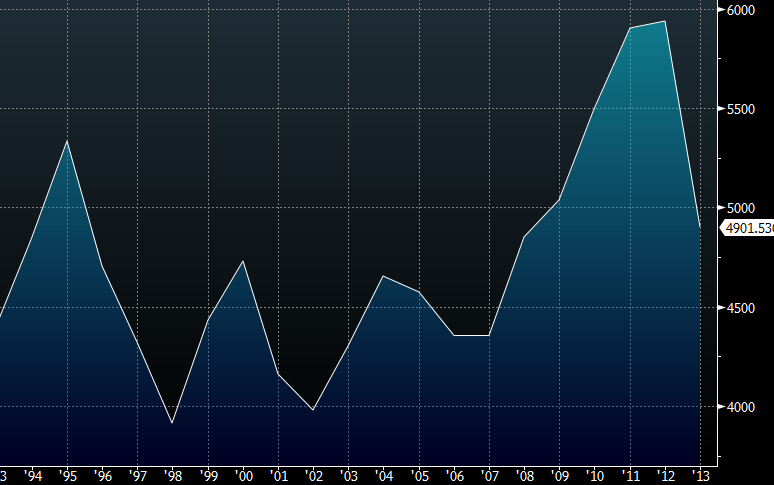

If you want to know what the next 20 years will look like, see the last 20 years in Japan. With the recent fall in the yen, Japanese real GDP in USD terms is now lower than it was in 1994, according to World Bank data.

Japanese real chained GDP in US dollars

It gets worse from there.

Japan has had the benefit of low private debt and extremely low inflation — two things the US and eurozone don’t have.

Worse still

A huge demographic headwind is coming due to aging populations. In about 2019 it’s the tipping point where there are far too few young workers to support the aging population.

It won’t take that long to rock the global economy. At the moment, Wall Street can ignore the obvious and looming problems but once the stock market stops climbing (it doesn’t even need to fall) the party will come to an abrupt end.