Why you should be cautious of your financial advisor

I come to write this piece because an approaching retirement friend has just sold his London house and has a relatively significant amount of money to invest. As he trawls around wealth managers I have offered him some basic financial advice but the thing that I find most startling is that all these advisors (almost without exception) are still telling him to hold around 30-50% of his wealth in bonds. To me this highlights the dangerous dominance of (the flawed) Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT).

MPT was developed by the Nobel Prize winning Harry Markowitz and was published way back in 1952. Essentially it describes the best theoretical portfolio for a person’s tolerance for risk. Mathematically it maximises return by mixing together different asset classes. It concludes that diversification reduces risk which intuitively it sounds right. But as I have written before about economics and finance, the mathematical illusion of certainty that this model gives, is perilous. The model is fundamentally flawed and must be used with extreme caution.

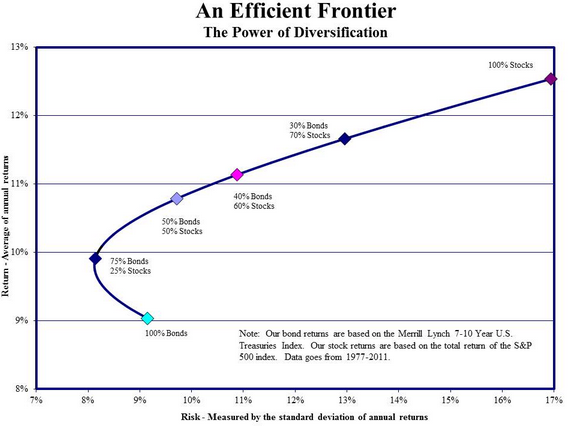

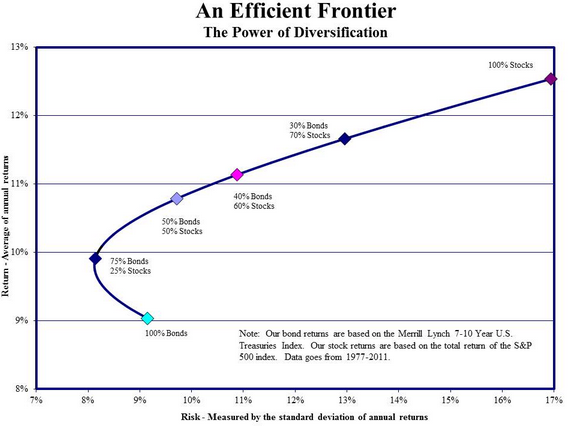

source: Young Research and Publishing

Note that this efficient frontier is based on data from 1977 to 2011. The line produced would vary significantly depending on the years chosen (which is the problem).

What you can see from this graph is that the lowest risk (on x axis) is not 100% bonds but actually 25% equities and 75% bonds. Why? Because the price of equities and bonds do not move together. This is the mathematical expression of the benefits of diversification. But this is a very simple portfolio with just two assets classes – US equities and US Treasuries. Clearly there are many more, for example UK equities (big cap, small cap), German corporate bonds, French high yield bonds, Japanese property, private equity etc. Most asset allocation models include many different asset classes.

At the MPT’s mathematical heart though, is the correlation coefficients of different asset classes – the degree to which different asset prices move together. So for example a correlation coefficient of 1 between US equities and bonds says that if US stocks move up 1%, bond prices also move up 1%. A correlation coefficient of zero says there is no relationship at all between the performance of the S&P 500 and US Treasuries. And a correlation coefficient of -1 says that if the S&P 500 moves up 1%, US Treasuries move down 1%. Most correlation coefficients though are somewhere between the extremes. However the problem is that these relationships are inherently unstable – correlation coefficients vary over time, a lot. For example, the price of gold has been both positively and negatively correlated with equities depending on the time horizon chosen. In the financial crisis, the risk on risk off trade ensured correlations were significantly different than in the past. Thus the benefits of diversification were significantly less than theoretically predicted and many investors lost a lot of money in the crisis because of the MPT’s flawed assumptions. The real problem with MPT is that it assumes a relationship between asset classes that is not stable. It is based on past correlations that are unlikely to hold up in the future.

I’m not the only one who fears the dominance of the MPT in financial thinking. Scott Vincent of Green River Asset Management says “MPT relies on a number of unrealistic assumptions” and yet “regardless of MPT’s shortcomings on both a theoretical and empirical level, its dominating influence will not easily be dislodged. MPT is deeply woven into the fabric of our financial system.”

In response to Scott’s article JJ Abodeely warns that “…the basic tenets of MPT shape the decisions of nearly every institutional money manager, wealth management firm, investment counselor/consultant, and financial planner in profound and often disturbing ways. Your money is almost certainly being managed with these ideas at the core. The traditional approach to asset allocation is built on false axioms.”

And MPT does not just fail with regard to correlation coefficients, it has many other drawbacks. It takes no account of asset valuations: it ignores the fact that currently bonds are highly over valued (thanks to QE). We have experienced a 30 year bull run in bonds and convexity ensures bonds are highly vulnerable to rising rates (I have blogged about this before). MPT ignores the fact that equities, as any stock market historian will tell you, have long periods of outperformance and long periods of underperformance. “Average” yearly returns can be calculated but bear little relationship to reality. Essentially the numbers that are inputted into the mathematical MPT equations – average long term asset return, asset risk (its standard deviation) and of course correlation coefficients – are all highly uncertain and vary massively over time. And yet the ultimate asset allocation that comes out from these equations is highly sensitive to these numbers (which are of poor quality). Yet again the illusion of mathematical certainty leads to misguided and over confident choices. However as the entire wealth management industry bases much of its decisions on MPT, then all are making similar mistakes. So relatively there is little difference between them. Good for the industry, less good for those whose wealth is being managed.

And yet Asset Allocation is the most important decision in looking after your wealth. It is far more important than deciding which stock to buy. Most analysis suggests that 80-90% of performance comes from asset choice. It is why a friend of mine – Justin Urquhart Stewart – when he set up his own asset management firm (7IM) choose to focus his teams’ efforts on Asset Allocation and not active stock selection.

A good wealth manager will take the MPT and treat it with caution it deserves. Any model that forces an investor to buy overpriced assets (bonds) cannot be doing a good job. “Historical performance is no guarantee of future returns” is a warning on all financial marketing material. But the entire fund management industry sells its products based on this premise: “buy last year’s top performing fund”. And it seems, asset allocation decisions are based on the same misguided belief that the past predicts the future. Maybe human beings have an inherent dislike of the uncertain world we live in and try it tame it through modelling. However self-awareness, the ability to recognise that false reliance makes both a good fund manager (as well as trader).

I will end this week with a quote from Albert Einstein:

“As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.”

Substitute finance for reality and it hits the mark.

By the way, I’m currently reading a biography of Einstein by Walter Isaacson and I thoroughly recommend it.