Germany has so far played the eurozone crisis perfectly — using the cheapened euro to support its manufacturing industry — but it could be the victim of its own success as growth picks up.

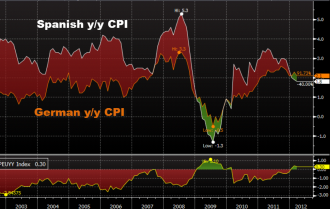

Today Bundesbank leader and ECB governing council member Jans Weidmann said monetary policy for Germany is too expansionary. On Thursday, German April preliminary CPI is expected at 2.2%; that compares to 1.8% in Spain. Other than at the height of the credit crisis, German inflation hasn’t been higher than Spain since the advent of the euro.

Weidmann is right and complaints from Germans about inflation risks are something I expect to hear loudly repeated in the future. Germany alone would likely have rates 1-2 percentage points higher yet the main refi rate is set for the entire region which is grappling withnegative growth and generational unemployment.

Weidmann may not be a hard-liner like his predecessor Stark but he’s still a German central banker. To climb the ranks at the Bundesbank your DNA has to be hard-wired to prevent a restful night of sleep when any inflation threat creeps in.

Maybe the first signs of inflation will appear in this week’s data, maybe not. It doesn’t matter because inflation is caused by that special combination of low borrowing costs, growth and low unemployment. With unemployment at a record low in Germany and ECB near the absolute limit, Germany is two-thirds of the way there. And if a report in today’s Die Welt is credible, Germany will soon hike government growth forecasts.

When central bankers keep rates too low for too long, problems are inevitable. In the era of austerity, greater regional growth disparity is also inevitable.

In almost any scenario, German economic growth and inflation will outpace the periphery in the coming 3-5 years. This means that a showdown between the low-growth low-inflation periphery and high-growth high-inflation Germany is also inevitable.

In the buildup to the crisis rates were kept lower than they should have been for Spain, contributing to the Spanish housing bubble and banking imbalances there. At that time, rates were too high in Germany which was struggling with labor reforms.

This time the roles will be reversed, which makes a good night’s rest much more difficult for a Bundesbanker.

I can’t envision a scenario where the ECB raises interest rates to combat German inflation — no matter how loud Weidmann protests. Such a move would directly increase the cost of periphery borrowing with countries teetering on default.

It’s almost impossible to predict how improperly low rates but it’s a certainty that there will be negative consequences for Germany, whether it shows up in banking, housing, runaway inflation or some other part of the economy.