The minutes of the FOMC meeting "shocked" the market this week, after the Fed said that they would look to decrease the Fed's balance sheet.

That typically comes from letting the maturing issues on the balance sheet run off without replacing them with new buys from the Fed. Since the start of the QE, the Fed has not only been buying US issues, but also replacing maturing issues by buying an equal amount of the maturing debt.

The unwinding of the balance sheet- at least for now - does not necessarily mean outright selling of issues on the balance sheet. However, that can be another "tool" employed by the Fed if they really want to put on the brakes and steepen the yield curve in the process. For now that will not be the case.

So what do we know?

Overall, we know the Fed is worried about inflation, and to combat that the Fed is starting to tilt its monetary policy (rates), toward higher rates, and also is looking to reverse QE stimulus. More specifically:

- The Fed is tapering the balance sheet buys, and will be finished with that action by the end of the 1st quarter. Currently the Fed continues to buy both treasuries and agencies

- The Fed is looking to tighten 3 times in 2022. The expectation now is up to 82% that the Fed will tighten for the first time in March by 25 basis points. The market is pricing in a 69% chance for a 2nd hike in June and 58% chance for the third hike in September. There is also a now 50% chance for a 4th hike in December. The market is pricing in more hikes at least in the Fed Funds contracts

- The Fed is looking to let the balance sheet run off as well but that process will be slow (the Fed is not looking to have the balance sheet go back to zero any time soon).

What does the 3rd action imply? More specifically, if the Fed will not replacing maturing issues, how much of the Feds balance sheet runs-off next year? What is the actually amount?

That amount will - all things being equal - require the outside market to step-in in lieu of the Fed buying.

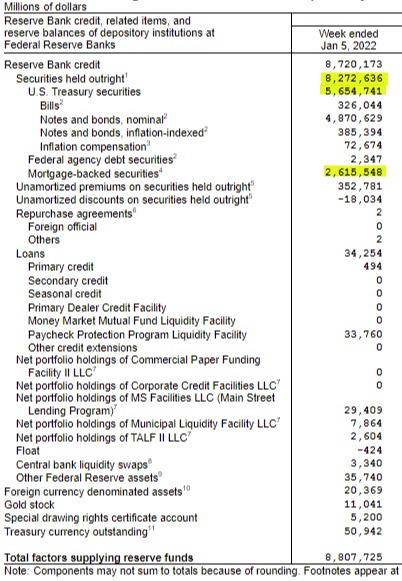

The current Fed balance sheet has 5.654T of US treasury securities and 2.615T of mortgage-backed securities. Those are the securities that the Fed has purchased through quantitative easing. The total of both is 8.269T.

How does that balance sheet compare to the total auction amount by the treasury?

According to the treasury, they auctioned off at $17.791 trillion of securities in 2021.

So with a $8.269 trillion balance sheet and an auction total for 2021 at $17.791 trillion, that sounds like a huge step up for the "market" to absorb in addition to the normal auction amount.

The answer to the question is "no it is not" (or not as bad as it looks) as long as the Fed does not outright sell assets from its balance sheet.

The market will only need to absorb:

- The buying the Fed currently does from QE all things being equal.

- The maturing issues that will run off next year

That leads to the next question which is "what is maturing over the next 12 months?"

Looking at the maturity structure of the Fed's balance sheet and more specifically the holdings of US treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, the total of maturing treasuries up to one year currently totals:

- 71.797B within 15 days

- 334.601B within 16 to 90 days

- 727.418B from 91 to 1 year

The total maturing in a year is $1.133T of the $8.6T balance sheet or 13.18% of the balance sheet. All things being equal, we can expect the Fed balance sheet to be somewhere in the $7.5 trillion range at the end of the year.

Of the total auction total in 2021 ($17.791T), it represents 6.3% of the total auction amount that "the market" will need to absorb (1.133T/17.791T auction amount).

The total of mortgage-backed securities maturing within one year is only 35 million - hardly any at all as mortgages are longer out the curve. The mortgage portfolio should be near unchanged at the end of the year.

If $1.133 trillion will run off, what happens to rates as a result of losing that buyer?

Looking at the weekly changes in the Fed Balance sheet, in the current week, the Fed was selling (tapering) in the short end. The weekly holdings of those bills fell by -17.26B(see 2nd yellow line on the table above). They have been buying 16-90 day bills (+14.381B) and 91 day to 1 year bills (+12.601B). They sold 4.14B of 5-10 year notes, but bought 2.868B of 10 year or over and 556M of 1-5 year notes.

So currently, most of the Fed buying is 1 year or less (at least this week). That amount would in theory at least, have to be absorbed by "the market" Yes, there are fed buying in the 1-5 year and over 10 year, but they are currently being offset by net selling in the 5-10 year. The Fed seems to be reducing slowly the longer end of the balance sheet (and may continue to do so down the road, but it will be modest sells).

With the Fed looking to tighten at the time of the balance sheet runoff (1st tightening in March and more after), the investors in the market will be rewarded with higher bill rates for absorbing the Fed buying that will disappear. That is the cost of the QE and the unwind, but is also a benefit as it will hopefully slow inflation too.

The longer end should not have to absorb much of Fed balance sheet run off UNLESS the Fed says it will outright sell larger amounts out the curve (reverses QE and does Quantitative tightening or QT instead. The Fed has the balance sheet to do that).

Will they do do QT? It is always a possibility especially if inflation gets really out of hand. Is it likely? Not expected but you never know.

Can the longer end still move higher despite the Fed not outright selling longer maturities?

Yes, of course.

Real rates are too low and investors have started to demand higher longer term rates to offset the higher inflation rates which seem not to be transitory at all. The 10 year yield is up 25 basis points this week alone.

How high can will rates go?

That is the $24,000 question, that the "market" will decide over time. However, seeing 10 year rates up to 2% to 2.75% is not out of the question if the Fed Funds rate is going to 1.0% to 1.25%. All depends on inflation (and maybe overseas rates as well).

SUMMARY: Overall, the word this week that the Fed will look to decrease the balance sheet is more of a scare than substance, given recent balance sheet changes, and the expectations that it will not be doing QT. However, the action was helpful in pushing rates higher across the curve (which is a good thing to slow inflation).

The reality of the balance sheet announcement is it will be most impactful in the shorter end, where the Fed is also looking to attract capital by raising rates.

The hope is the transition will indeed raise rates, but slow inflation, and keep demand for US issues steady.